The Full Story:

Something subtle, but major, happened this week.

The US Federal Reserve has officially inverted their long-term policy strategy from containing inflation to promoting inflation.

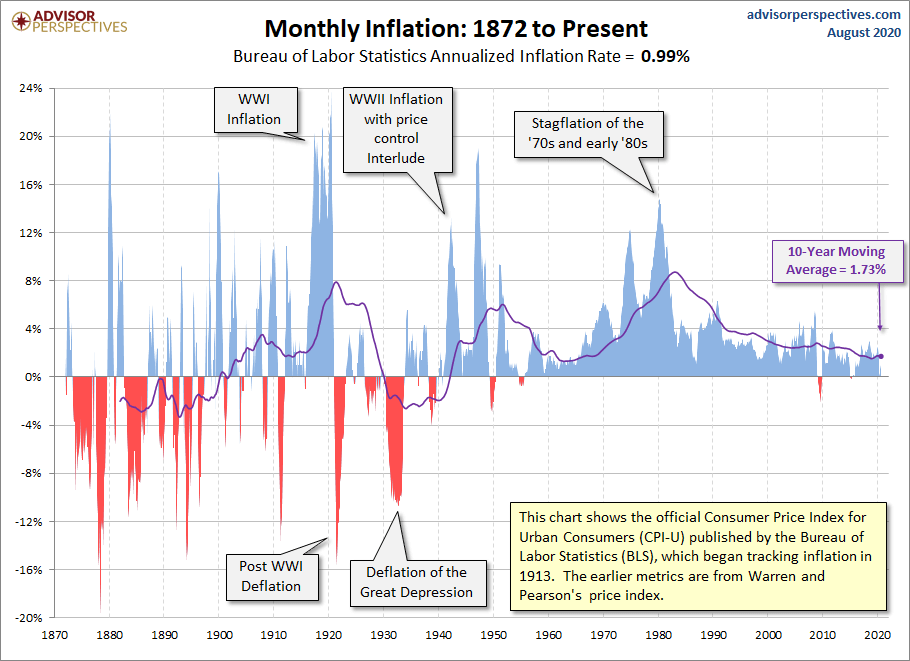

Now for some perspective. The US Federal Reserve didn’t get into the inflation management business until we fully abandoned the gold standard in 1971. Prior to that, Congress would try and micromanage inflation rates through price controls and interventions. This was a clumsy process that distorted marketplaces and created dueling periods of inflation and deflation around the gold standard peg. During the “Guns and Butter” spending binge of the 1960s, the US suffered from persistent inflation which led some of our trading partners to demand conversion out of dollars into gold. It was this run on the gold window that forced Nixon to close it. This promptly led to even higher inflation levels as the world adjusted to the newfound fiat status of the US dollar. Economics caught up breathlessly. Study shifted away from fiscal economic management and moved toward monetary economic management. The US Federal Reserve operated with limited credibility without fiat management experience and didn’t get control of inflation until Fed Chairman Paul Volker declared war on it in the early 1980s by deliberately putting the US economy into recession. The Volker inflation-hawk era transitioned into the Greenspan inflation-management era in the 1990s as the Federal Reserve became adept at maintaining inflation around 2%. Under Bernanke and Yellen, 2% inflation became an explicit target and an implied ceiling. But, in the current Chairman Powell’s opinion, setting 2% as an implied ceiling only encouraged lower inflation expectations and, therefore, lower present inflation. Here is a visual summary of US inflation’s journey since 1872. Pay special attention to the rapid deterioration in inflation recently, and the persistently downward slope of the 10-year average:

The antiquity of the Bernanke/Yellen 2% inflation ceiling framework became very apparent last year as the Fed over-tightened monetary policy in anticipation of late economic cycle inflation that never arrived. At W&A, we saw this mistake in advance, as did many others (including President Trump), but the Fed continued to rely on the Volker framework that had proven effective over the last 40 years. While markets might like the Fed to be nimbler of opinion, the Fed must be careful not to appear erratic as shifting postures could erode credibility and confidence. But frankly, the lack of inflation accompanying a 3.5% unemployment rate after a decade long economic advance confounded Fed economists and prompted Chairman Powell to initiate a wholesale reappraisal of orthodoxy. To maintain marketplace credibility, a change in orthodoxy requires dutiful analysis, conclusion consensus, and a measured and consistent communication campaign. Powell began the campaign on Thursday.

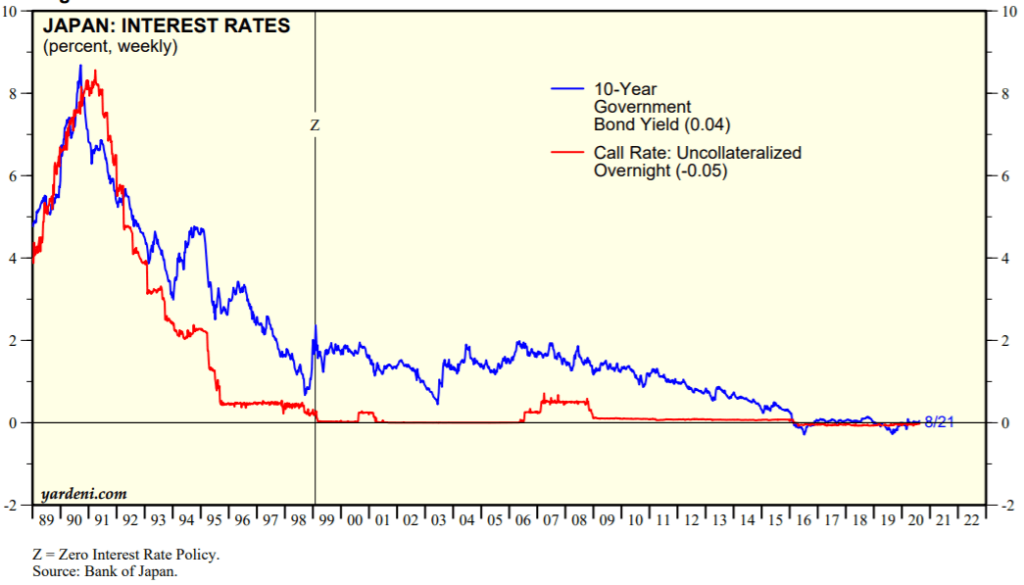

The world has changed substantially over the last 20 years. Most notably, global population growth rates have fallen from approximately 2% in 1980 to 1% in 2020. Economists project population growth rates to fall to .5% by 2050. Since population growth rates and labor productivity rates determine economic growth rates, a significant downshift in population growth translates into a significant downshift in potential economic growth (without a significant upshift in productivity growth). Lower economic growth rates reduce monetary velocity, inflation rates and subsequently interest rates. Look to Japan for proof. Demographic erosion has led Japan to maintain a zero-interest rate policy since 1999:

Additionally, the amount of money printing and securities buying (also known as quantitative easing) the Bank of Japan has deployed over time dwarfs the controversial recent actions of the US Federal Reserve. Currently, the Fed holds $7 trillion in assets purchased by money creation on its balance sheet. The Bank of Japan holds $6 trillion. Seems equivalent until you relate those amounts to the size of each economy. Japan’s QE assets approximate 125% of their total economy, while the Fed’s QE assets approximate 34% of our total economy. In sum, the extreme erosion in Japan’s population has required the Bank of Japan to peg its overnight interest rate at zero for the last 20 years and maintain continuous quantitative easing to defend against deflation. (Deflation is bad primarily because real debt burdens grow in deflationary environments, disincentivizing taking on new debt. This leads to economic deleveraging and lower economic growth rates in a pernicious cycle). According to Jerome Powell’s testimony on Thursday, the Fed now believes the demographic forces plaguing Japan have become widespread enough worldwide to warrant a complete inversion in Fed orthodoxy. The Fed has thereby transitioned from an inflation-fighting institution to a deflation-fighting institution.

For investors, the implications are massive. First, the Fed has signaled that interest rates will remain anchored near zero indefinitely. Since asset valuation levels derive from interest rate levels (would you pay more for a house with mortgage rates at 2% or 20%?), persistently low interest rate levels support persistently high valuation levels. Using shorthand, a 1% interest rate supports a 100 P/E ratio for the stock market, a 2% interest rate supports a 50 P/E and a 3% interest rate supports a 33 P/E. US Treasury yields have averaged 5.5% historically, correlating with the 17.5x long term average P/E for the market. What should the stock market’s P/E be if investors believe US Treasury yields will average 2% over the next 20 years? Second, more money printing means more demand for assets. Conceptually, if the Fed uses the money it prints to buy all of the US Treasury bonds issued, investors would have to use their money to buy other stuff. This “crowding out” creates more demand, and higher prices, for non-Treasury assets. Additionally, buying Treasuries from banks frees up more loan capacity which translates into more speculative capacity. In a bathtub with an open tap, all the rubber duckies rise!

Whether this shift in strategy remains permanent will depend upon its success. Powell suggests the Fed revisit its long-term assessments and strategies, in depth, every five years. Five years from now, Volker-ism could reassert itself, but between now and then the Fed wants inflation… and that’s bullish for investors.