The Full Story:

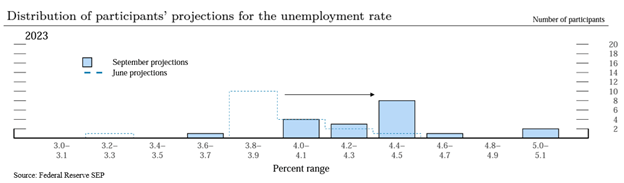

The market’s obsession with the inflation rate this year will migrate to the unemployment rate next year. The Fed has pulled the hand brake on economic growth, and it’s working, so the pace and extent of employment market damage will become their focus. In their September Summary of Economic Projections, the Fed forecast a median unemployment rate of 4.4% for 2023, within a range of 3.7% to 5%. This projected range shifted notably to the right (more unemployment forecast) versus their June projections, as seen in the chart below:

On December 14th, the Fed will release updated projections, likely revealing an even higher expected unemployment rate for 2023. Various Fed speakers have drawn attention to 5% as a healthy unemployment level to rebalance labor markets and relieve wage pressures. Unfortunately, monetary policy lacks precision. Using comparisons of their past projections, the Fed finds a 1.3% margin of error in their past unemployment forecasts. Applying this margin of error to the 5% derives an upside risk of a 6.3% unemployment rate compared with 3.7% today. This calculates 2 million lost jobs at the 5% target and 4 million lost jobs with the error margin applied. Clearly, the stakes are high.

A Federal Reserve deliberately inciting recession to “rebalance” labor markets will undoubtedly draw political rebuke. This dynamic plagued the 1970s as lawmakers pressured the Fed to ease conditions with every uptick in the unemployment rate. They complied and extended the duration of toxic inflation. Chairman Powell has warned his handlers that he will not kowtow like Arthur Burns and to expect more vigilance.

So, as we enter 2023, let the games begin!

The Fed wants 2-4 million additional Americans out of work. Most likely, those American voters don’t want to be. Will the Fed err on the high side, or will political pressures force them to err on the low side? We shall see. But expect this storyline to gain momentum. To prepare, let’s survey the labor landscape today and baseline this brawl for 2023.

To 5% and beyond!

First, add workers!

The United States has 265 million working-age citizens: 158 million of which are employed, 6 million of which are unemployed, and 100 million of which have simply opted out. For the purposes of calculating the current unemployment rate of 3.7%, the 100 million “not in the labor force” get excluded. Many of these individuals have retired, but others could rejoin the labor force as COVID benefits, and cash reservoirs run dry.

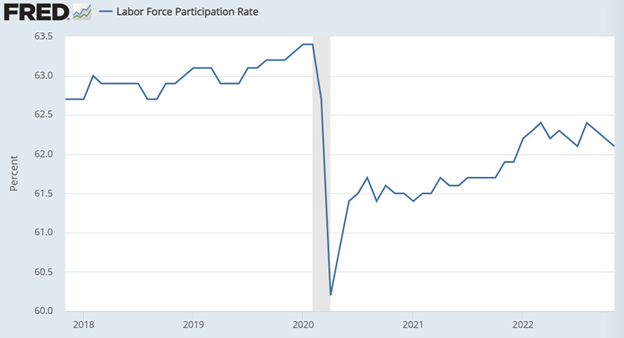

To increase the unemployment rate, the Fed either needs to drive up the number of people in the labor force while holding the number of jobs constant, or it needs to reduce the number of jobs available while holding the number of workers constant, or some mix thereof. Unfortunately, labor force participation has been stubbornly low since the pandemic for a variety of reasons. Consider the trend below:

Labor force participation pre-pandemic peaked at 63.4%, compared with 62.1% today. That 1.3% drop amounts to 3.4 million workers that, if inclined to rejoin the labor force tomorrow, would boost the unemployment rate to 5.5%. Mission accomplished! Clearly, adding laborers to hit 5% rather than cutting laborers to hit 5% is preferable, but unfortunately, historically, the trend is not our friend. Typically, in recessions, participation rates fall.

Second, cut jobs!

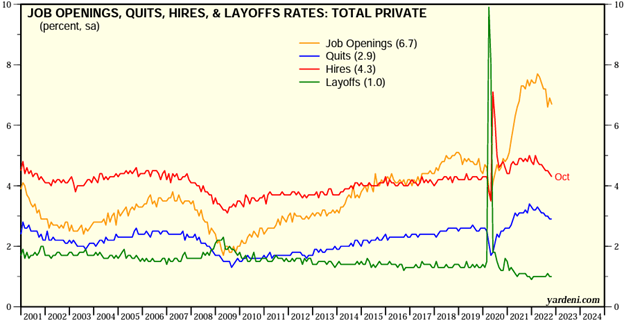

A couple of things happen before an enduring rise in the unemployment rate appears. First, the labor market develops a fear of the future. This is revealed in fewer people quitting their jobs and fewer job openings. Second, hiring slows as anxious businesses trim budgets. Third, layoffs commence as the economy shrinks and businesses are forced to purge. The Bureau of Labor Statistics releases the Job Openings and Labor Turnover survey each month. Within this survey, we catch a glimpse of the trends referenced above:

As evident, quits and job opening measures have already begun their descent, indicating labor market anxiety. New hire measures have also started their descent as management shifts from reaching for revenue to preserving profit margins. Layoff measures remain flat as the reality of recession hasn’t forced separations yet.

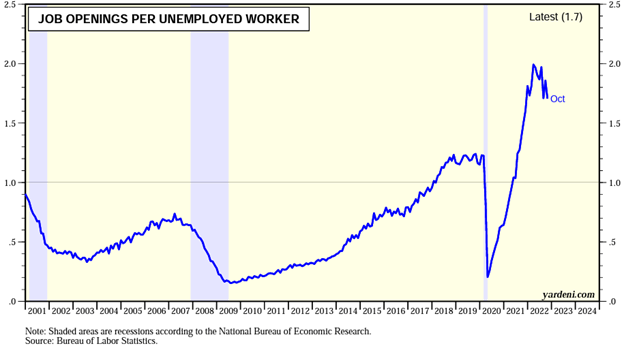

Some may wonder why the layoff news flow hasn’t levitated the 3.7% unemployment rate. This is due to the continued imbalance between labor demand and supply. The jobs available across the economy well outnumber the workers available, meaning those laid off become quickly reabsorbed. This chart chronicles the number of jobs available for each unemployed worker:

While this number has clearly peaked, demand for workers still well exceeds supply. This number must fall further before displaced workers begin driving up the unemployment rate.

Lastly, many economists claim that employment trends remain robust, signaling that the Fed must raise rates substantially higher to cool things down. We disagree. Not only have early indicators revealed growing softness in the labor markets, but the government’s own employment surveys have as well.

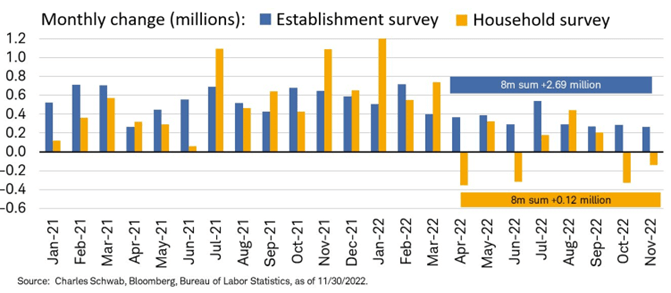

On the first Friday of each month, the government delivers its Employment Situation Summary. They pull data from two primary surveys. First, they call companies and ask how many workers they have, how many hours they are working, and how much they are paying them (known as the Establishment Survey). Simultaneously, they call households and ask if they are working, looking for work, or have opted out (known as the Household Survey). Both contain employment counts, but in recent months, the surveys wildly disagree:

According to the Establishment survey, businesses claim to have hired 2.7 million people since March. According to the Household survey, only 120,000 people claim to have been hired. They can’t both be right! Overall, seasonal adjustments and multiple job holders can distort the Establishment survey, making the Household survey the purer ground-level read. By this measure, the labor market isn’t nearly as firm as feared.

In sum, the Fed wants a higher unemployment rate in 2023, and based on our analysis; they will get it. From here, it’s all a matter of degree.

Have a great Sunday!