The Full Story:

Aside from the crypto crash, investors remained fixated this week on the existential threat of inflation. Per the narrative, higher overall inflation will mean lower profit margins and lower valuation multiples. The prospect of lower margins and lower multiples should alarm investors as those heady headwinds could limit, if not reverse, investor returns. As studious investors, we take note of daily investor anxieties, but we never accept narratives at face value. After donning our green eyeshades and digging deeply into the data sets, we have some encouraging information to share on the historical relationship between inflation and investment returns.

The Gold Standard

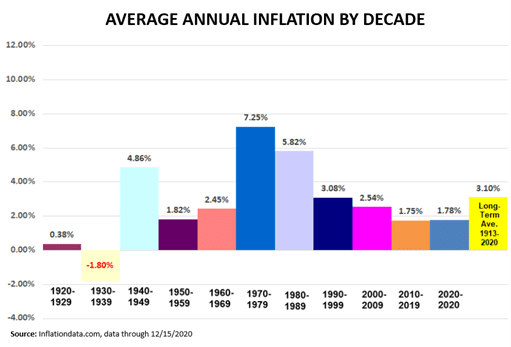

After years of pernicious deflation during the Great Depression, FDR officially removed the gold standard in 1933. By executive order, holders of gold and gold certificates had to convert them into US currency, backed by gold, at a fixed price of $20.67 an ounce. Once the Federal Reserve became flush, they raised the conversion price to $35 an ounce, effectively increasing the money supply by 69%. The dollar remained pegged to gold at $35 an ounce until markets forced Nixon to remove the peg in 1971 after LBJ’s guns and butter spending spree. Other than the economic distortions caused by WWII, the US experienced very little inflation until the late 1960s.

The Fed Standard

The transition from gold to fiat led to a significant and prolonged adjustment period while the US central bank learned how to manage inflation and inflation expectations. From 1971 to 1980, inflation in the US averaged 8.1% per year, with gold peaking in January of 1980 at over $850 an ounce. To break inflation, Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volker raised interest rates to 20% by March of 1980 and left them there for a year. This created two painful recessions, but established the US central bank’s credibility as a powerful and determined inflation fighter. The Fed effectively became the new gold standard, with inflation running 2.6% on average for the last 30 years.

The War on Deflation

The Federal Reserve and their overseas counterparts fear that the combination of globalization, digitization, and population deceleration trends will create a persistent and pernicious downforce on general price levels. To offset these deflationary forces, central banks have resorted to unorthodox policies such as quantitative easing and negative interest rates. Japan has deployed the most aggressive and inflationary policy mix and yet still suffers from a deflationary undertow. The US Fed’s longer-term deflationary concerns more than offset their shorter-term, supply shortage induced inflationary concerns. Hence, their message anchoring around current inflation as “transitory”. Strategically, the Fed has opted not to fight the battle on current inflation in order to win the war on future deflation. In our opinion, widening the macroscope lens supports their controversial stance.

Inflation and Investment Returns

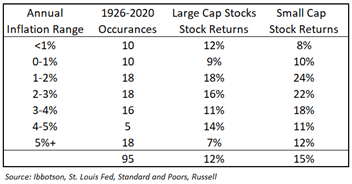

I have provided this perspective to establish that inflation/deflation and their management responses have varied widely over the last 100 years. Even still, investors have managed to compound money at double-digit rates over the entire time frame. Furthermore, the annual rates of return often seem impervious. Consider the data below:

Clearly, markets can rise in any inflationary environment, refuting the assumption that inflation kills margins, multiples, and investor returns. The highest average annual returns occurred when inflation ranged between 1 and 3%, but double-digit returns occurred all the way up to 5%+. Surprisingly, in 1980, inflation averaged 12.4%, and yet large cap stocks advanced 33% while small cap stocks rose 40%. Inflation may influence investor returns, but it certainly doesn’t determine them.

Now, to diffuse the emailers who will cite real (inflation-adjusted) returns as the proper measure, I agree mathematically but not in practice. For individual investors, inflation amounts to changes in spending levels, not general price levels. The real returns for investors equals nominal investment returns minus their own drawdown rate, a portion of which may offset rising inflation but not all. At home, spending decisions determine overall inflation rates and therefore net, real returns.

Have a great Sunday!