The Roaring 2019s

We began 2019 with a very bullish forecast. We blamed the Fed’s dual tightening activities of interest rate hikes and quantitative tightening for generating the liquidity crisis that precipitated a 20% market sell-off at the end of 2018. We expected Fed Chair Jerome Powell to reverse course to rectify the mistake or risk forcing a stable economy into recession. If not, we expected President Trump to find ways to stimulate growth while kicking off his 2020 election campaign. Not unprecedented… historically, it’s the third year of the first term in the Presidential cycle that generates the highest annual returns (19.2% on average). Lastly, thanks to the Trump Tax cut that took effect 1/1/2018, corporate earnings grew 23% in 2018. Pairing this with the 20% year-end decline in prices produced very attractive valuations for investors entering 2019. On cue, global equity markets rose over 12% in the first quarter of 2019, followed by another 3.5% gain in the second quarter. Soon after, President Trump began significantly escalating his Trade War rhetoric. Trade volumes and manufacturing activity collapsed, yield curves inverted, and recession probabilities began rising. Our trusted Leading Economic Indicators signal rapidly declined toward the zero-bound, leaving us wanting for a potential $1 trillion stimulus package to interrupt the market and economic descent. Dubious that a $1 trillion stimulus package would materialize, we cautiously hedged out some of our equity market exposure over the summer. Then… surprise! On October 11th, the Fed quietly announced a $1 trillion open-ended quantitative easing program (dubbed QE4). This led us to reduce our hedge and enjoy the market’s reflexive rally. Since QE4 began, the Fed’s balance sheet has now grown 11% while global equity markets have rallied 12%. As an aside, one must wonder if Trump’s Trade War had the intended or unintended consequence of forcing the Fed into another $1 trillion round of quantitative easing. We may never know, but… nothing buys votes like notes!

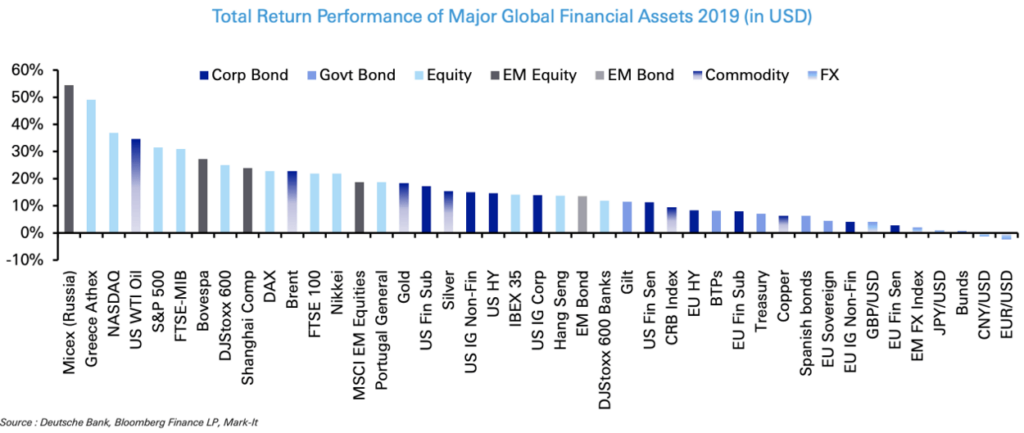

As a result, by year-end 2019, EVERYTHING made money:

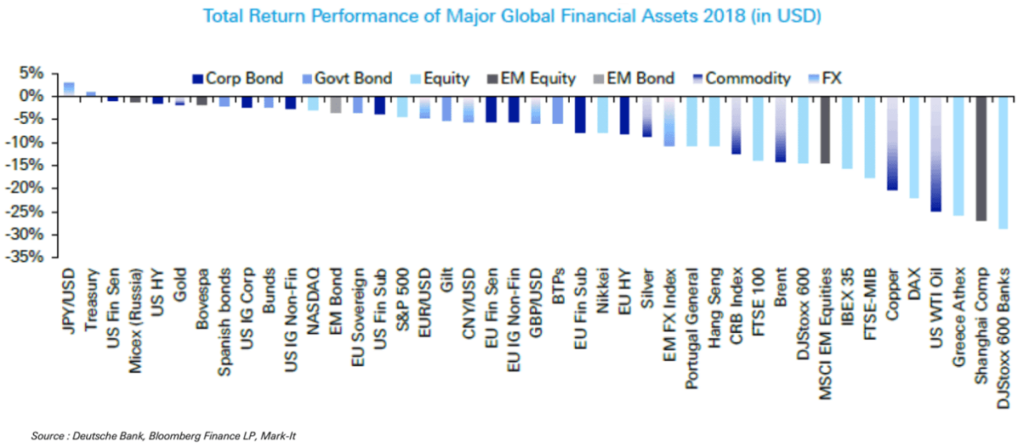

In stark contrast with 2018 when virtually NOTHING made money:

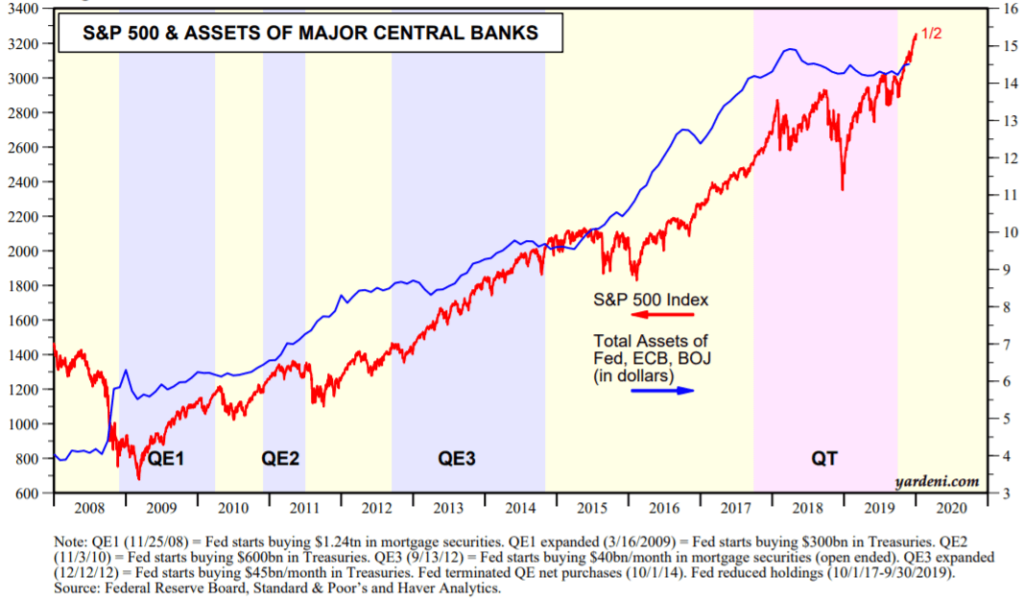

See what a difference the Fed can make?

Recessionary 2019?

Modern markets have basically become proxies for global liquidity levels. Fearful of trade-induced recessions, central banks worldwide eased policy in 2019 at levels previously reserved for financial crises. By the end of the year, global central banks cut rates over 50 times while the US Fed, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan all reignited asset purchase programs. Nothing sums up the correlation between central bank liquidity injections and stock market performance like the chart below:

Note that the QE highlights only refer to US Fed actions. The blue line combines the liquidity injections from the Fed, ECB, and BOJ. While the Fed took 2015 and 2016 off, the European Central Bank redoubled their purchases. The only period of coordinated liquidity retreat from the major global central banks occurred beginning in early 2018, which also corresponded with a durable top for the global stock markets as highlighted below:

Inflationary 2020?

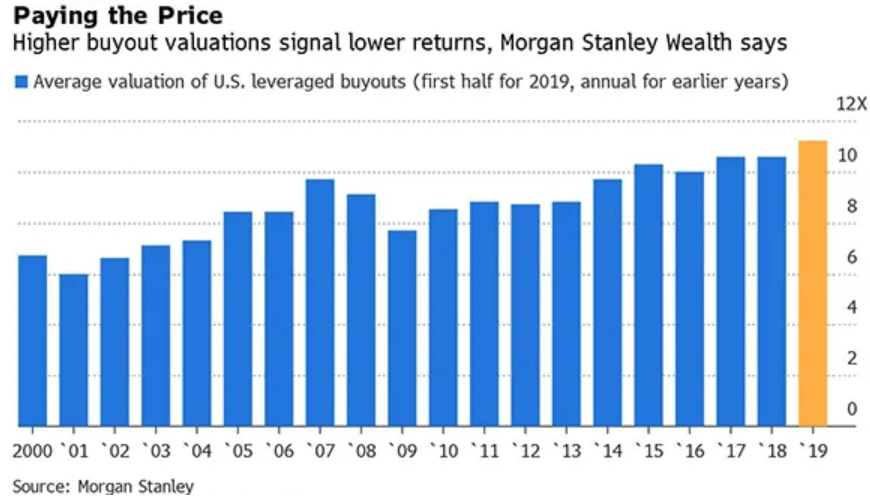

Can the global central banks permanently forestall recessions and bear markets with infinite liquidity injections? Not without consequences. According to the textbooks, when the supply of money exceeds the demand for money, inflation ensues. If these liquidity injection levels persist, the biggest risk for 2020 won’t likely be recession, but inflation in the prices of goods and services and/or inflation in the prices of financial assets. Fortunately, inflation levels for goods and services worldwide are currently benign. Economists attribute this to a host of factors including cautious consumer sentiment, globalization’s supply chain efficiencies, and technology utilization’s price compression. Unfortunately, inflation levels for asset prices are not benign. Public sector valuations haven’t recaptured their 2000 level highs (yet) but their private-market counterparts have well exceeded them:

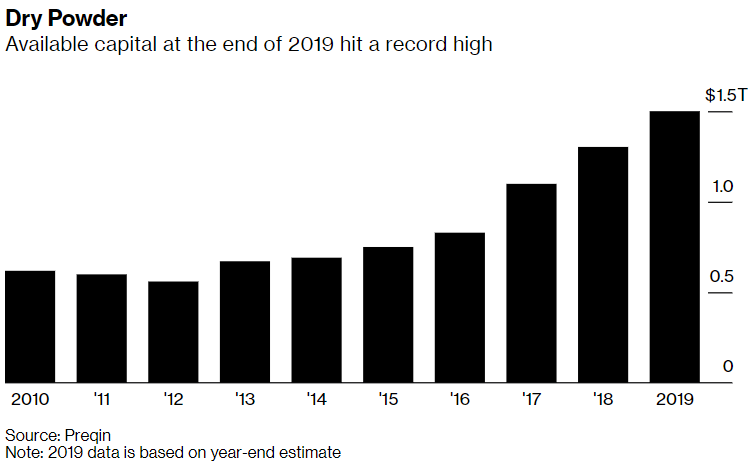

Furthermore, the amount of capital awaiting deployment at these prices has reached a record high:

By definition, asset bubbles occur when investment capital becomes fearless or investment fads become irresistible. As we enter 2020, if global central banks remain committed to low rates and large-scale asset purchases, the greatest risk for investors may not be a market decline… but rather a market advance.